Written by A.S.

Autonomous Student Network – University of Texas at Austin (ASN-UTA)

On August 2nd, the University administration released new aspects of its plans to modernize the University for “security” purposes. These plans include restricted hours for building access and new surveillance systems with proximity card readers and video cameras. To raise awareness, the administration has adopted the cutesy slogan “Your ID is Your Key,” to encourage students to have their UT IDs on them at all times, in order to have access to buildings during restricted hours.

This move on the part of the University, disguised in the rhetoric of student safety, should be read as a University strategy to securitize against the threats to the power of the administration, not defense for students. What threat is the University responding to? The most recent act of violence on campus, the stabbings on May 1st, was carried out by a UT student. Furthermore, some of the worst threats to the safety of the student body are other students, divided as the student body is by the lines of class and social war. Wealthy elites denigrating and exclusion working class students, white students attacking students of color, catcalling and sexual assault, queerbashing and transphobic harassment are all symptoms of the internal divides and power relations that make students unsafe. Coincidentally, these are the threats the University consistently fails to respond to or hold people accountable for.

Instead, the University’s strategy for “safety” is one of enclosure and control. Enclosure in the sense that a putatively “public” University functionally becomes privatized–only those who pay their way in can have access to space or resources. Modernized entrances and ID cards become the fences closing off access, eradicating the potential for the University to be a site of the commons or a public good. This is both laughable for an institution that prides itself on serving the public and yet to be expected from an institution built on land stolen first from indigenous peoples and then stolen again from black and latinx Austinites.

This is a strategy of control in that it solidifies the administrations power and capacity to surveil its own subjects–the students–while separating out and exiling what it and the power interests it upholds have deemed undesirable.

Rather than keeping students safe, this new system is primarily aimed at keeping out homeless folks who may try to inhabit these spaces, whether to use their resources, take shelter from the weather, or simply to occupy public space. Implicit in this is a belief that homeless people are threats to students, exemplified by the anti-homeless sentiment that spread like wildfire in 2016 after the murder of Haruka Weiser. This relies on a classist and racist stereotype that casts homelessness as deviant and inherently violent, since homeless people deviate from the idea of a good citizen-worker who has the capital to afford a place to live. Therefore, the very conditions that force homeless people to find more public places to occupy become the conditions from criminalizing and removing them from public spaces, leaving them with fewer and fewer spaces to go. These new policies exist on a continuum with the everyday harassment homeless from police people near campus experience for “trespassing” by existing or for trying to make ends meet by panhandling, or the litany of stores that restrict access to restrooms to customers only.

At the same time, this new policy exercises control over students themselves. The combination of proximity access chips, card readers, and video cameras constitute an apparatus is used to identify students. An apparatus is a particular way of exercising power, one focused on the regulation of society in order to maintain order and “peace.” An apparatus works by simultaneously identifying subjects and making them recognizable to systems of power, and by distinguishing those who deviant from the norm by their distance from it. An apparatus exercises power at a micro-level in how it causes bodies and subjects to change their everyday actions and movements.

The new technologies deployed by the University are an apparatus because they identify the “student” and differentiate it from the non-student through identity cards. It shapes the movements of this subject group by requiring the daily practice of ensuring the student brings their ID to campus and forcing them to go through the bodily motions of producing their ID card to unlock a door. It distinguishes students from non-students by inciting these subtle (or perhaps not so subtle) bodily motions. Furthermore, these systems force a non-student attempting to enter these buildings to change their bodily motions–by sneaking in behind someone else opening the door, by hoping that the doors are slightly ajar and unlocked, or by acquiring ID cards themselves–all in full view of surveillance cameras which can be retroactively used to identify and target non-student individuals.

It further makes students identifiable through the little known regulation that UTPD can ask any person on campus to produce a student or staff ID, and that if they fail to do so they can be asked to leave or charged with trespassing. Clearly meant to police the presence of homeless people, this rule has also been deployed against students. When masked student antifascists confronted and chased off fascists attempting to flyer on campus in the middle of the night, UTPD demanded they produce IDs or leave campus. UTPD even indicated that if those who refused to ID themselves were seen on campus again, they would be stopped and asked to identify themselves or risk being charged with trespassing.

All of these strategies are useful to the University because information is power. Being able to identify and separate students from non-students enables the policing and purification of spaces. It enables the University to also target those students who may attempt to refuse identification in order to avoid surveillance by the state or fascists due to their organizing work. It enables a low-level proliferation of surveillance that tells the Universities where students are at all moments and when buildings are being accessed–information that can be used both for profit (by making renovations to buildings with high student traffic, or setting up recruitment and advertising in those areas to inundate students with propaganda) and for punitive measures (by tracking who may have accessed a building to engage in subversive activities, whether revolutionary work or simply existing as a criminalized subject in a violent carceral society).

All of this is part of a broad trend of normalizing surveillance on campus. The proliferation of cameras and the reworking of public spaces to remove foliage and increase visibility goes hand in hand with a state and corporate desire to be able to know where individuals are at any moment and who is using public space. While seemingly benign, we’ve seen from such events as the prosecution of the UT Antifa 3, the hunt for the fraternity vandals, and attempts by the administration to discipline student activists that these police powers are meant to preserve the kind of “peace” that allows the University to continue business as usual–a condition which normalizes the everyday struggles and suffering of students of color, queer and trans students, women, and working class students on campus while criminalizing their attempts at resistance.

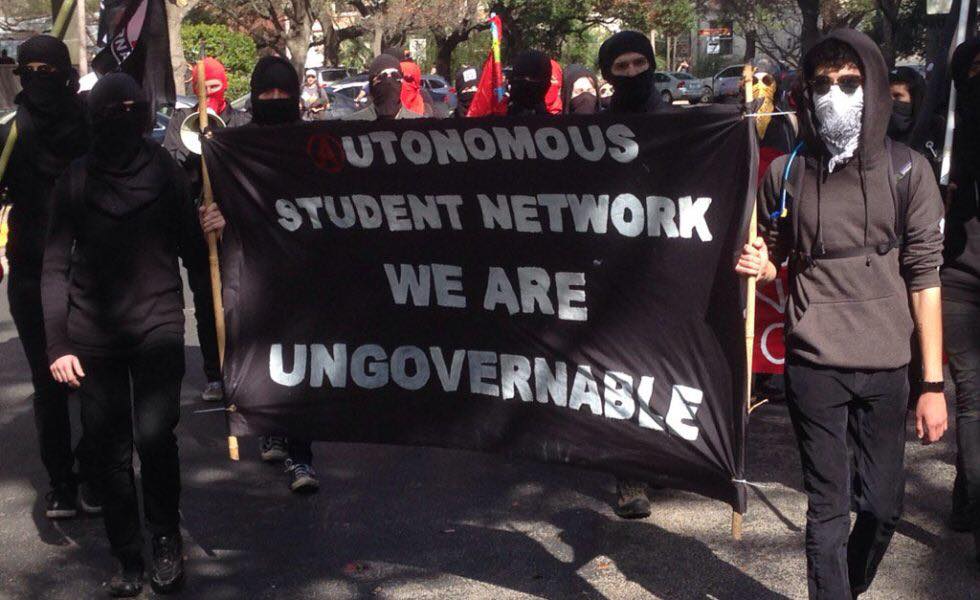

In opposition to this, we must find ways to refuse identification and surveillance. We must evade the University and its attempts to capture us. And in doing so, we must find a space to reclaim an a commons against the University, the undercurrent of resistance that reclaims space, time, and labor from the administration the State, and Capital for shared practices, collective knowledge, and an openness that builds new relationships beyond the limits of the University. We do this when we remove our information from the directory, refusing the University’s right to control and release our information. We do this when we put on masks, obscuring our features and refusing to identify as students of the University. By refusing identification, we evade the University’s attempt to leverage disciplinary power against us for our allegiances to revolutionary work and those excluded from the University. In doing so, we express a solidarity with all of those the University leaves out by refusing to uphold the elitism of our status as students. Instead, we seek to disseminate the resources we can access and implode the privileged status of the University from within, to open up a space for the excluded–the homeless, the criminalized, and all those excluded from access to the University. When we mask ourselves and become anonymous, we open up a space for a new collective solidarity amongst ourselves that does not require the administration–the solidarity of mutual defense, de-arresting, a shared militancy, and a revolutionary love for transforming this world. We make a promise–in the streets and in our lives–to fight for each other, to support each other in our struggles with work, harassment, discrimination, and everyday violence until we have gained our autonomy and liberation from both the administration and all the violent structures of this world.

As we struggle, we must cease to be students–or to solely be students. We must became nameless and faceless. We must become an unidentifiable mass, a collective held together and defended by its bonds of solidarity and support–one that can never be dispersed or dispelled by the police of this world. Instead of being Somebody for the University, we should be Nobody. When we are Nobody to the University, we can form something else, be something else in a way that builds our collective power and our relationships. By refusing to be the person the University wants or expects us to be, by being somebody (or Nobody) else, we open up the possibility for true transformation.

I’m Nobody, who are you?