https://www.facebook.com/ASNTX/videos/1995472730693042/

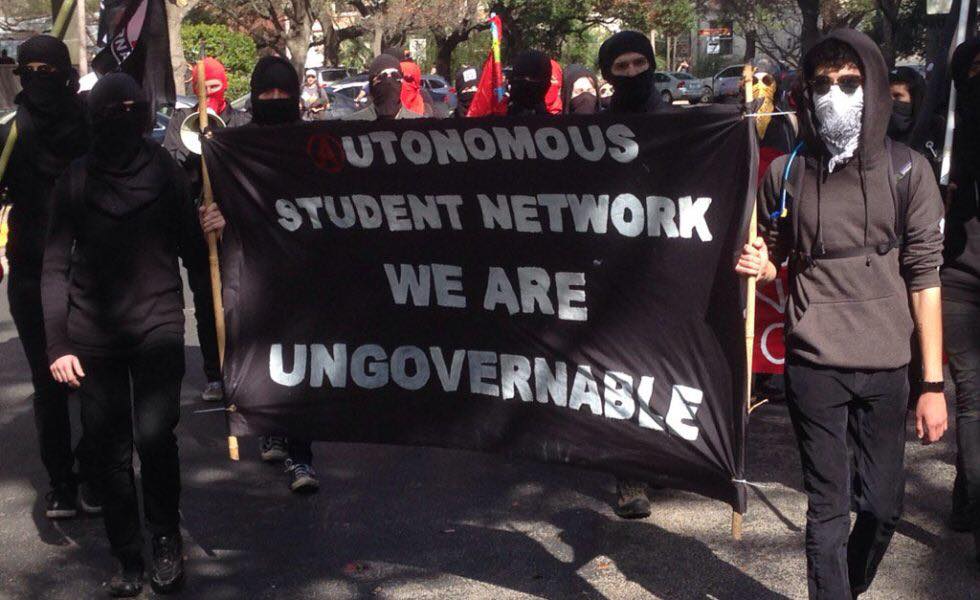

Originally published on the Autonomous Student Network – UT Austin website.

“The present catastrophe is that of a world actively made uninhabitable. A sort of methodical devastation of everything that remained liveable in the relations of humans with each other and with our environments.”

—The Invisible Committee, Call

It has been one year since the collection of friends associated with this project called the Autonomous Student Network began to respond to The Call—the call to get organized, to begin to Spread Anarchy and Live Communism.

We have engaged in struggles and conflict—and they simultaneously engaged us, changing us deeply at the level of both our organizational composition and our unique subjective experiences. Old members have left our collective, and just as many new ones emerged to take their place with increased energy and militancy. We’ve lost friends, made new ones, and rekindled connections with friends we thought we had lost. We’ve made it through about one year of the absurdist, neo-fascist presidency of Donald Trump—itself a symptom and symbol of a deeply destructive, collapsing civilization that thrives off our alienation, immiseration, exploitation, death, and ecological devastation. This system is known by many names—Capital & the State, Empire, Modernity, Europe, The Leviathan, The Gendered Nightmare, and many more.

Many have taken to calling themselves “Children of the Catastrophe” in order to name our present condition. We find this a little too grandiose and disheartening, and prefer to take a slightly more joyful approach. We are Children of the Ruins, children who are playing amidst the wreckage of history, finding our way and exploring new potentials, new confrontations, new chances for escalating the conflict with the present socio-politico-economic paradigm. By joyful we do not mean some misplaced optimism or utopianism that is oblivious to our present situation. Instead, we are describing an orientation that is creative in its engagement with the world, that emphasizes intensities (of relationships and experiences) which transform us and our environments, that experiments with uncertainty, and strengthens our capacity to care, love, & fight all at once. We take an irreverent approach to the catastrophe, recognizing the significance of our historical moment and the forces we face yet refusing to be submerged in exhaustion or burnout over every crisis that we cannot stop. Instead, we play amidst the ruins to find new friends, experience our own powers, build collective capacity, produce new ways of fighting & living, and recompose the social fabric that has been either shredded or put in the service of Capital. At every moment our play helps us chart a course out of the impasse that all existing institutions have presented us with.

After a year of play, we find it necessary and helpful to reflect on what we’ve experienced—the situations we’ve been part of, the conflicts we’ve witnessed, and what we and others have accomplished. As students, we believe a focus solely on our struggles would miss so much of the insurrectionary moments and potentials that exceed the University as a site of struggle. We hope to build ties and be present for these moments of insurrectionary refusal, moments when we can act against our interests and positions as students and begin to act towards the destruction of the University–which has always been a colonial, capitalist factory for the production of citizen-subjects. As such, our reflections encapsulate not only struggles we have directly initiated or been involved in but ones that we have witnessed that sent shock waves through our communities and the city, opening up fractures within the present social organisation. We offer our words and analysis as one perspective among many, hoping it will expand the field of future possibilities and inspire further confrontation with this world—or at least the desert that is Austin, Texas.

Spreading Anarchy

“To say that the war against Empire arises from everyday life, from the ordinary, that it emanates from the ethical element, is to propose a new concept of war stripped of all its military content.”

—The Invisible Committee, Spread Anarchy, Live Communism.

The past year exposed new fractures and fissures in Empire, as the disorder of our social “organization” has made itself clear to those who once held faith in it and has made itself more urgent to those who never held any illusions about it. In these moments, we have witnessed and sometimes engaged in confrontation with a goal to escalate the conflict, to deepen the fissures that make modern society possible and to open up the possibility for something else. This year’s confrontations—and our first major presence—began with the Inauguration Day protests known as J20. Alongside comrades from the Revolutionary Student Front we marched from an undisclosed location in West Campus towards the Tower, filling the streets and the air with militant banners and chants while completely avoiding the police’s ability to predict and control us. We carried this militant energy into the student rally, where we engaged in propagandizing and defending the march from fascist agitators like Stratton Gaines, who drew a knife and yet was not charged by UTPD.

On J20 we also encountered and struggled against one of our first “leftist” obstacles to the insurrectionary moment. In our J20 reportback we failed to name them directly but we will name them now. The International Socialist Organization and the United Students Against Sweatshops had hijacked the planning for J20 from the coalition we had been a part of (ATXResists), going behind the group’s backs with zero transparency or any attempt to reach out to or inform many of our organizations that had wanted to be involved. By January many of our organizations were expected to come to an event that had already been planned out for us.

This planning of course exhibited a distaste for the uncontrolled and insurrectionary potential of the day. A march leading us through highly inaccessible, construction-filled chokepoints and stairs paired with a series of energy-killing speeches that served as no more than a walking reading group. A parade through downtown surrounded by cops with little disruptive potential. Great resistance on the part of ISO & USAS organizers to suggestions from others to deviate even slightly from their route to be a little more disruptive. Perhaps most damning of all was their redirection of the student protest’s energy into the evening’s OneResistance rally, a permitted, cop-collaborating march whose organizers had actively condemned and criminalized revolutionary and masked protestors alongside the police. This rally’s hatred of revolutionaries was so strong that when a militant bloc attempted to follow behind them, the march sped up to get away and even left behind many of their disabled members—whom the militant bloc then took in. OneResistance never even got to go to the Capitol thanks to the last-minute decision of their police escort, who took them on a nonsensical route through downtown.

Just as J20 set the stage for the insurrectionary potential of a new age of rebellion, it left divides that would inform the rest of the year—especially on campus. Lasting tensions with groups like the ISO continue to limit and inform working relations between campus groups. Supposedly leftist organizations continue to propose that we restrain ourselves from militant actions until we reach the proper threshold for a “mass movement.” Militancy remains so disparaged by these groups that even the suggestion to share information about masking and security culture is met with contempt.

In contrast, we believe every moment is ripe with insurrectionary potential and that we ought not wait—for permission, for the proper “historical moment,” or some “critical mass.” This is not to imply some adventurist or reckless jump into insurrection or revolution—that would be a self-destructive proposal. Instead, we propose escalating conflict by exploring the situation, experimenting with our capacities, taking actions that increase the intensity and energy of the moment, and finding new ways to act with others to accelerate the insurrection and add fuel to the fires. In this process we remain open to the unexpected and spontaneous happenings which may exceed ours or any professional activist’s predictions & control. And we continue to refuse those who would impose a limit on our movement and kill our momentum.

We ourselves have spent the year finding strategic points at which to engage in the everyday war which defines modern civilization. In an expression of revolutionary solidarity with NAIC’s Indigenous People’s Week, we executed a banner drop with a militant decolonial message. We mobilized crews over the year to eradicate fascist graffiti in West Campus. Alongside other student groups, we stood with Defend Our Hoodz/Defiende El Barrio against the gentrifiers at the Blue Cat Café, a yuppie cat café that has also become a haven for Neo-Nazis who protect it. Fighting against gentrification, we also courageously defended each other from arrest and confronted the police and fascists protecting the café. At every stage we have aimed to actualize the message of the J20 uprisings: to Become Ungovernable.

Beyond our efforts, we have seen astonishing attempts at ungovernability shake Austin. In April, a series of acts of vandalism against fraternities shocked the UT community. The Vandals, as they called themselves, released a statement and were only ever seen masked on video surveillance, never to be identified. The police were dumbfounded, the fraternities were shaking in their boat shoes, and the administration further fanned the flames of student rage as they offered levels of support that most students could only dream of (ironic given the same administration claimed that they could not hold a frat responsible for a racist party because it was not a “UT institution”). The Vandal’s soon disappeared from memory, but their call for people to self-organize and “name your enemies” was answered in the fall. Slightly before the crest of the #MeToo movement, UT students began to name rapists and abusers in the community through twitter threads and facebook groups organized for the protection of women & queer folks. This level of student self-activity was not unprecedented—this was simply a larger scale manifestation of the everyday survival strategies of students who keep each other informed about toxic people. This all came to an end officially once Title IX got involved and the abusers tried to retaliate through administrative means, shutting down the facebook groups—but the fervor and the sentiment remains, waiting to bubble over in the next manifestation of self-organization.

Perhaps the most remarkable show of militant self-activity, yet one of the least discussed, is the Rundberg Rebellion of February. In response to the ICE crackdown on undocumented immigrants and recent raids, a spontaneous mass protest developed over multiple nights among the Latinx community at the intersection of North Lamar and Rundberg. This would come to be unlike any protest held by either liberal activists or the traditional Left. Dozens to hundreds of people filled the intersection, waving the flags of various countries. Many ran laps around the intersection, jubilantly dancing, clapping, and chanting things like “No rules, No ICE, let’s fuck this shit up!” As people took over the street, many stopped their cars and joined the action. Rather than another overdone street rally, the revolt took on a jubilant and defiant nature as an entire community manifested its social life in the intersection.

The police came out in full force and riot gear, terrified of the true potential of the insurrection that was developing, but they could do little but watch. Their arrival produced confrontation, with the militant youth launching water bottles and whatever debris they could find. While many Austin revolutionaries had arrived to participate alongside the community, they were not the first to mask up—it was the youth who donned masks and initiated confrontations, contrary to the assertions of many activists who have claimed that masking (and even militancy) are alien to Latinx and immigrant communities. These young insurrectionaries even defended the other militants against the anger of others who wanted the protest to retain a more peaceful, controlled nature. Though massively outgunned, the revolt did not need to defeat the police militarily because it had already won at a social level. The consistency, the social connections and community produced in that space—which one comrade described as “reclaimed…totally autonomous from the State”—ensured that the State could not penetrate or reclaim the territory until the people dispersed of their own volition.

Fireworks lit up the night and the celebratory crowd—with some reports even saying that a building and a cop car were burned over the weekend. Music blared through the night and produced a full-fledged dance party in the street. In an intersection ringed by riot cops people danced and sang along to “Fuck Tha Police.” Despite attempts by some to turn this into a moment to proselytize about their revolutionary program, the insurrectionaries maintained a jubilant and joyful revolt. They learned their politics not through lectures or books but by through experimentation and actualizing their capacity to hold space, through the rhythms of music and the movement of their bodies. Eventually though, this moment came to a close as over the next week the energy dissipated back into the community, the streets were not as filled, and the police seized upon certain community “representatives” to control the event while claiming that the confrontations were the result of “outside agitators.” We of course know that this is a lie—a racist lie that obscures the militant desires and self-activity of the exploited and excluded against the white supremacist State—and we know that the insurrection lives on in the community, in organizational efforts like the Instituto Tejano, and that it can always reactivate.

For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. The reaction came to us first in the form of fascist activity on campus. A series of racist flyers posted by American Vanguard in February, many calling for a “Muslim-free America” or asking people to report undocumented immigrants, followed by a lackluster administration response that called them “politically divisive,” stoked mass student anger. When the administration attempted to hold a townhall on campus climate, we worked along side our comrade organizations in the ATXResists coalition to attack the event by taking over the speakers lists and exposing the University’s façade of inclusivity. We heckled administrators and right-wing speakers and interrupted the clean spectacle the University wanted. Let us be clear—this townhall was nothing more than a Spectacle, a well-rehearsed theater in which students of color were the actors, an image which mediates liberation from white supremacy through an image of diversity that belongs on UT advertisements and brochures—all the while the administration continues to let racist violence go unanswered.

When the fascists attempted to come to campus again in April, we were there along side our Revolutionary Student Front comrades to stop them. As we stumbled upon them in the midst of a midnight flyering run, we pursued them and chased them right off of our campus. We prevented most of their flyers from going up, and the video and information we would get that day ended up being instrumental in the doxxing and subsequent firing of one Neo-Nazi, Sydney Crabtree. Yet, we found out soon afterwards that we had just missed running into a more threatening group of four American Vanguard members who had flyered and taken pictures of themselves Sieg Heil-ing in front of the MLK statue on campus. As the anti-frat vandalisms struck later that month it incited anger from the fascist right, who proclaimed their intention to recruit from fraternities and “preserve Western civilization.”

May Day—a day of celebration for the old worker’s movement—would become a dark day for us in Austin. Following the stabbings on campus and one student’s death, reactionary forces surged and took hold of the crisis to direct it at their leftist opponents. People falsely claimed the attacker was “a member of ANTIFA,” that the stabbing was part of a plan for the day’s revolts, and that Greek life was being targeted. Facebook pages came under scrutiny and any militant posts, alongside the provocation from the UT Vandals, were held up as proof to opportunistically target the Left. That evening, a militant “Red May” rally was surrounded and outnumbered by fascists who, with the leniency of the cops, took the opportunity to attack protestors, prevent the march, and even point their rifles at some of our comrades. However, that dark May Day did not break our spirits—it only strengthened our resolves to intensify the struggle against fascism and to build our capacity.

The city’s antifascists would have their chance at redemption on June 10th, when the fascists mobilized for Act for America’s “March Against Sharia Law.” Trained and armed with makeshift shields and flags, the militant antifascists and the mass mobilization that came out that day shut down any chance of an effective rally. The air rang with militant slogans and mocking chants of “What happened to your march?” At one moment, a chorus of megaphone sirens gave rise to a spontaneous electronic dance party, as the front line defenders began to move and shake while continuing to stare down the line of riot cops that had come to defend the fascists and attack the counter protestors. We hold onto these moments of joyous confrontation fondly, as they mark our capacities to think and create revolt outside the tired old scripts of the traditional Left.

This victory would mark a turning point, after which the fascists would retreat into secretive, unannounced rallies for fear of being shut down. After the battle in Charlottesville, local neo-confederates cancelled a September rally. In November, Patriot Front (the heir to American Vanguard) held a flash mob torch rally on the UT campus which we witnessed, but they have yet to stage an open and publicly announced rally. When they did show their faces again, such as at a December 9th anti-immigrant rally, they were again shut down, heckled, and chased off by better organized antifascists.

Just as the fascist right has kept up its attacks on Austin and the UT campus, the administration has escalated its efforts to stifle revolutionary activity. Organizers have been targeted with disciplinary hearings and warnings for their militant activity. One student organizer has been arrested and banned from campus for false claims of assault after being targetted by UTPD. UT police remain obsessed with attempting to identify and control student organizers, going so far as to implement new bans on masks and flag poles that could be considered “weapons.” They have cited false sections of UT rules to attempt to make protestors identify themselves. They spring into action to confiscate poles and escort protestors off campus for violating rules. Yet they let a group of Neo-Nazis from Patriot Front finish up their masked torch light rally and leave with all their flag poles, even as they spent minutes burning a patch of grass to put out their torches. Bureaucrats from the Dean of Students have similarly continue to undermine our organizing efforts and those of groups like RSF by selectively enforcing or fabricating rules about propaganda and tabling while taking down any flyers left on billboards. Meanwhile, groups like the Young Conservatives of Texas, corporate advertisers, and even groups like SURE Walk violate these rules constantly without repercussion.

The gap between the UTPD officer and the student carrying out the orders of the administration is small, as their effect and purpose is the same. The regulation of space is intrinsic to the order of the University, built as it is on the enclosure of common space & the colonization of land. Managing the uses of space ensures the management of bodies and their activities. The entire raised garden system in the West Mall–deceptively named the “Free Speech Zone”–exists primarily as an obstacle to mass student rallies. Despite claims about defending free speech, it is evident that if you use space or speech incorrectly—to challenge the administration or find new, creative uses of space—you will be targeted for disrupting the rhythms of University life. Similarly, you could observe all the protocols the University has and still be targeted simply for being a disruptive entity.

As we move forward in our attack on the University and the social order it reproduces, we must take into account these spatial considerations. Understanding the terrain on which we operate is essential to our activities. We have little hope or desire to establish some strong hold in the sterile streets of downtown Austin or on campus, and so instead we aim to attack and Spread Anarchy. Our attacks produce new fractures in the edifice of social order, new ruins which we can inhabit as the catastrophe that is this society intensifies. Our tactical maneuvers break with the suffocating peace of Empire and produce new forms of disorder, moments of interruption in which we can find each other and escape this dying world for another.

Establishing Presence

“Being in a world. An ability to be open, affected by the details and movements of a world. To be present is to be here. To oppose presence to representation is first and foremost to side with the living against the processes and techniques that administrate the environments of life.”

—The Institute for Experimental Freedom, Between Predicates, War.

Inseparable from our offensive attacks are the ways we have established our roots in the terrain of campus and Austin, the ways we have announced our presence and built the foundations for new ventures and new offensives. The question of infrastructure—of spaces, tools, and networks—is a necessary one to answer for any who hope to sustain an insurrection between spectacular moments of revolt. In particular, we approached this year hoping to overcome the defining problem of reproducibility and longevity that has long defined student formations—the problem of their dissolution once their members graduate and their inability to grow, connect, and survive beyond their radical subculture.

Perhaps our most successful attempt to overcome the problem of reproducibility came in our freshman recruitment drive. After our summer recruitment campaign, we received an influx of interest from new first-years as well as older students who newly discovered us. They brought with them a renewed energy and dedication to building the work we were already engaged in and expanding the scope of our activities. Many quickly took on prominent roles and activities in the organization and discovering their own capacities. We made our presence known more and more at demonstrations, with the number of black flags ever increasing and our members enthusiastically taking up the tasks of confrontation themselves.

Our presence became further known and felt through the relationships we established with comrade organizations and the actions we took together—groups like the Palestine Solidarity Committee, Revolutionary Student Front, Queer & Trans Student Alliance, and many more. Our short-lived coalition known as ATXResists made surprising strides in its ability to mobilize student rage and respond. The most inspiring moment came in February when, after the fascist flyers appeared and we had disrupted the administration’s townhall, we held our own student-run townhall to introduce our coalition, engage a deeper conversation about the nature of white supremacy on campus, and deliberate on revolutionary solutions to the problems. An assembly of over a hundred students filled the room to express their frustrations and hopefully work towards some form of student self-organization and power.

We simultaneously engaged in the construction of our own infrastructures and capacities to varying degrees of success. We have begun to establish networks of material support and communication with allies who can help fund and support our work even while they may not be directly involved in it. We have increased our capacity to produce propaganda, thus sharpening our ability to recruit and to counter racist propaganda. We have gathered data and both exposed Nazis employed by the University and far right figures on campus who are laying the foundations for new reactionary formations like Turning Point USA.

In May we released the first edition of our zine, formerly known as The Call, which would come to be the centerpiece of our Autonomous Student Media project. Since then, the activity of our new members has resulted in the release of a second DisOrientation themed zine and the pending release of a third. We have also set up a website for independent digital publication, hoping to one day fill it with the writings of revolutionary and marginalized students. In the meanwhile, it hosts a couple of articles and a more expansive archiving project that aims to preserve the history of leftist activity on campus since 2016.

We progressed from carrying out two Autonomous Student Defense patrols in the Spring semester to executing over two months of consistent weekend patrols in the Fall. On patrols we have cop-watched, helped the arrested with legal aid, and offered students an alternative to SURE Walk and the police. Entering the fall, we developed a strategy for organizing our defense program that we continue to reflect on and refine. We have established relations with one community center in West Campus, and are establishing communication to expand our network of spaces. Perhaps our most successful Defense initiative to date is a radical text alert system, which demonstrated its utility to students when the administration failed to alert people about the campus Nazi rally while we did.

Of course, not all of our efforts have been perfect or successful in establishing our presence. Some actions revealed our limitations—whether the limitations of becoming too much of a milieu, or a naïve approach to organizing and mobilizing people, or an overburdening of our movements. For example, in March we attempted to host a townhall on rent and student housing as part of our Housing Solidarity Network initiative—an attempt to organize student tenants and combat the student housing crisis. Nobody showed up. Not only had we under-prepared for the event—sharing it primarily on social media and only tabling for it a week in advance—we had misread the student mood. While the racist events in February provided the agitation and energy to make the ATXResists townhall successful, student apathy with regard to the everyday problem of housing made it a non-issue that we had failed to adequately engage on. Our attempt to escalate that conflict and establish a presence died as we sat alone in that room and went off defeated to get dinner. Now, the Housing initiative remains a dormant project, as we have come to recognize that we had spread ourselves too thin and were overworking ourselves. Our strategic focus on our current projects has increased our capacity and success in our organizing. Yet they are not free of problems—for example, our Autonomous Student Defense problem is currently dealing with the problem of low recruitment for patrols and attempting to reorient its outreach and organizing strategy to deal with this.

Similarly, ATXResists died almost as quickly as it was born. There were problems since its inception. As a student coalition, it faced the problem of losing momentum every time a break period would hit. Winter break and spring break were the nails in the coffin, as the dispersal of our forces and the inactivity of group chats ultimately led to the silent death of the group. Furthermore, our attempts to have the coalition carry out its own projects and initiatives proved unrealistic. Many of us, already stretched thin between the pressures of our own organizations, school, jobs, and a social life, had little time or energy to devote to an entirely new coalition. Additionally, the group was burdened from the start with bureaucratic debates about how it would be structured, how votes would be decided, and hammering out points of unity—we even got trapped in votes about how we would vote to decide how we would vote! These problems reached the breaking point in March when, after the successes of the townhall, the coalition was unable to act on any of the discussion points brought up. Instead, we were caught in a series of debates about HOW to organize students and structure the coalition, which killed general interest and faith in our group. This followed by the inactivity that came with spring break sealed the fate of coalition.

There are lessons to be learned from these failures. Establishing presence and building a world is hard work, and it is important that we do not stretch ourselves too thin with an over-proliferation of projects. Similarly, it is important to act in accordance with our capacities and on whatever will expand our capacities. Avoid the tendency to bureaucratize and get bogged down in the question of how to make decisions—when we do this, we unwittingly reproduce the same form of governance we are fighting, an apparatus that incites us to think in terms of management and imposing decisions. Instead, we should build networks and relationships, cultivate our strengths, share skills, and converge where it tactically makes sense to do so. This is where the ATXResists coalition was most successful, as it brought us and many other radical organizations and comrades into conversation, setting up long-lasting relationships. We hope that with this new year, we can take the chance to revisit the coalition and restructure it so that it better fulfills our collective goals.

In all these initiatives, we have experimented with new modes of organization and experimental actions that break with the model of the traditional student movement. We are not asking the University for anything because there is nothing they could give us that we desire. The University is not something to be saved because there is nothing to save within it–from its inception it was a project for building new citizens, consumers, and guardians of social order that was built on the graves of the colonized and enslaved. The very function of the University is to produce a specialized class of people trained in the technical management of society, the application of governance which makes our lives an everyday hell. Similarly, we do not aim to merely take over the University’s functions and proclaim to make it operate “for the students.” We have no desire to inhabit the sad position of UT president Greg Fenves. Instead, we are acting for ourselves to re-invigorate a common life among students, to find each other, learn from each other, build with each other, and play with each other. Whether it’s a dance party in a park or an organization meeting filled with board games and casual conversation, we are constructing ways to organize that do not merely reproduce the regimes of work, control, and brutality that we oppose. We are finding new ways to imagine knowledge, community, life, and study. Cultivating knowledge without purpose, playful uses of space, community building, self-defense, and more actions lie on this continuum that begin from our current situation and move towards our refusal of the roles assigned to us.

This is what we mean when we talk about “student power.” Not student power to sustain the University and carry on its functions and their roles as students, but student power to build something that would abolish our roles as students–as professionals in waiting, as future managers and governors. We are building infrastructure, making connections, and providing for ourselves using pieces we have found in the ruins of this civilization. In our attempts at self-activity—whether in the form of media or anti-racist community defense—we hope to bring more students into an awareness of their own power to act, to produce transformative experiences that they will carry with them beyond the 40 acres, and to expand the terrain of struggle beyond the mere preservation of the student position within the University; we hope to move towards total struggle against the violent institutions which make this world and this University possible. Our play in the ruins, the tools we develop, the spaces we cultivate, the relationships we nurture, the communities we defend: all of these help us inaugurate and bring into presence a new world. This new terrain of life provides us a staging ground for our attacks on this world, and offer support and refuge against counterattack and repression.

We face the new year with a new penchant for building. As the world continues to burn, we are at least comforted and energized by the microcosm we are constructing and expanding here with each other and those friends that we encounter. Hopefully, our endeavors will achieve new levels of effectiveness and repopulate the deserted terrain of student life. And as we do so we will proclaim:

We’re Here, We’re Queer, We’re Anarchists, We’ll Fuck You Up!

Living Communism

“The only question for the commune is its own potentiality, its constant becoming. It is a practical question. To become a war machine or collapse into a milieu? To end up alone or begin to love each other? The commune does not describe what we organize but how we organize ourselves, which is always at the same time a material question.”

—The Invisible Committee, Spread Anarchy, Live Communism.

Perhaps the most difficult thing to capture in a reflection on the past year is the lived experience of the Autonomous Student Network: the ineffable the people, presences, places, and moments that have defined our playful adventures in the ruins. The lived relationships, ecstatic experiences, subjective transformations, and friendships forged exist outside of what can be captured and represented in images and language. Yet this is perhaps the most essential aspect of ASN. Somehow, against all odds—against the isolating pressures of the University, the divisive competition incited by neoliberal society, and the separation of students into an infinite array of social milieus and subcultures—we found each other and attempted to construct a new form of life.

At the center of our organization and its ethics is a deep appreciation for the unique, singular existence of each and every one of our members and our relationships—autonomous beings in an interconnected web of relationships and experiences that constitutes a world. When we go into an action we make sure every member has a way to safely get in and out together—we leave nobody to navigate the terrain on their own. We act as a team, developing our capacity to work together through experience and solidarity. As we began the year we introduced many new members to their first militant actions—their first masked demonstrations, first banner drops, first antifascist actions, and more. In each of these, we worked to ensure that everyone felt confident in their capacities and could participate safely as part of our group. Furthermore, we do not privilege the spectacularly militant over other activities. All capacities and interests have a place in our group, not just those willing to take the streets and face off with cops or Nazis. Finding ways to incorporate all kinds of capacities and modes of involvement has strengthened our work, has built new relationships, and has expanded our appeal.

Per our concern with reproducibility and community, we recognize and center the labor—emotional, affective, reproductive, and otherwise—that makes our life possible. Through our accessibility officers we are navigating the creation of more inclusive and fulfilling spaces as well as the mediation interpersonal conflicts. We have attempted to foster an organizational culture in which we can be honest about how we are doing, our capacity to be involved, and what kind of work we are prepared to do. We check in on one another and try to ensure everyone has the support and commun(e)ity they need. No one is expected to do something they are not prepared to do or prove their revolutionary credentials; we reject the anxiety-inducing self-surveillance produced in so many revolutionary spaces where one feels pressured to perform a revolutionary identity and thus are unable to say “No.” Our hope is that those who come to ASN stay because they enjoy it, because engaging with us is fulfilling and increases their capacity for life and action. Here you are not simply a passive member of an organization, but an active participant and essential part of a project that seeks to transform everything—including ourselves. We aim to be transparent in our organizing and cultivate in every person the capacity to work with others and fulfill their goals, rather than simply be lead.

In this process of living and acting, we encountered new obstacles and toxic realities that we have had to work through. Members whose inaction and inability to work with others left projects on hold and failed to engage people. Toxic and alienating behavior by those who would come to leave our organization while proclaiming themselves better anarchists than us. Crises of toxic behavior that threatened to fracture our group, leading us to develop and implement accountability processes to help navigate interpersonal violence and conflict. We have drawn upon feminist and abolitionist traditions of restorative and transformative justice, social reproduction, and power to inform and deepen our understanding of what it means to engage in combat against this world.

Moving beyond a spectacular or militaristic understanding of the war and conflict that we are in against this world, we understand that the ways we care for each other are themselves combative. That the relationships we cultivate and the intensities we share are just as essential and complimentary to our capacity to throw a punch or wield a firearm. To avoid becoming a new military and a new state, in our militancy we emphasize capacity building and relationships as much as attack and negation. As we transform ourselves, we open up new horizons and new potentials that escape, subvert, and negate the apparatuses of Imperial control and Capital accumulation.

This is what we mean by Live Communism. To think of communism no longer as simply a state of affairs to be brought about by a seizure of power, but a practical, everyday enactment of ways to cultivate relationships that bring more things in common—practices enable us to share space, time, labor, affection, and entire worlds with each other. Perhaps the best glimpse at our lived practice of communion or communism could be seen in our parties. Practically every action becomes an occasion for a social event—a time for decompression, reflection, and play. After our first action of the semester, our newest members were introduced to our organization by a massive after party, producing an intensity of experiences that helped solidify group solidarity and friendships that would continue to grow over the semester.

Over the course of the semester, we built our strength through our capacity to dance, sing, and play together. Whether sharing stories from the day’s events, supporting comrades after traumatic events or arrests, reliving some of our scene phases, or exploring new ways to transform a popular song into a song about Antifa, we find joy in the midst of the seriousness of our present situation. The classic ASN songs and dance routines that define our times together are rituals by which we conjure a new world and a new way of living with each other. Also, our parties are way more fun and affirming than any frat party.

A few people who came to our Halloween party in October are privy to this. Lit solely by the lights of oil lanterns hanging from a tree, we danced in the middle of Hemphill park, shared pie & drinks, and had some rambunctious fun—reclaiming public space in a celebration of the rebellious origins of Halloween and of each other. A friend who joined us described it as a “surreal” setting—a bunch of hooligans dancing the night away by lantern light in the woods. For a short time, we conjured a communist congregation, an example of what we could do together when we realize our capacities, act creatively, and have fun while we do it.

This project remains our focus for the coming year and the years to come. As we face a dying world—a world of economic and political crises, deadly fascist regimes, the lingering threat of escalating global conflict, and widespread ecological turmoil—it is more important than ever that we learn how to live. Even as crises spread, we must refuse to be consumed by them and continue to cultivate the relationships and forms of life that enable us to thrive. Our actions likely won’t be the deciding factor in creating the revolutionary changes that will fix the world—if it can be fixed. Perhaps we can be an inspiration to others, proliferating gestures and examples that can ripple out and help end the disaster we are living through. But even if we do not, this will all still be worth it because of the world we will have produced with each other, because of the solidarities and connections we will have built, and because of how we thrived with each other. We hope to make it through the coming years, and we hope that the Autonomous Student Network exists for years to come and long after our current members graduate and move on. But even if we do not, we will continue to play and celebrate, to live and fight, to dance and sing amidst the crumbling ruins of civilization. Every wreckage, every revolt, every abandoned building will become a new site of joy and creation. For this year and for every coming year, we will continue to

Spread Anarchy,

Live Communism!

We hope you will join us. Let’s find each other.

—The Autonomous Student Network